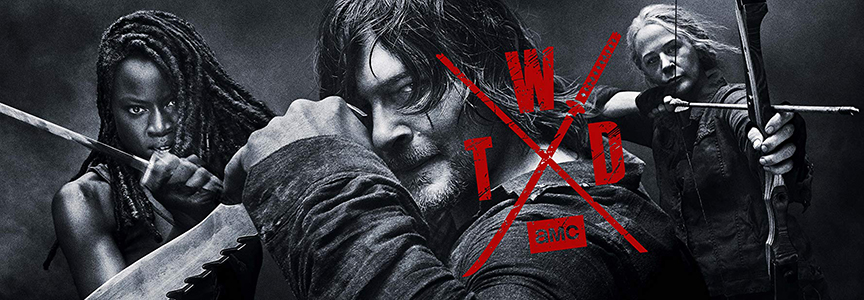

I chose to finally write about The Walking Dead after nine seasons because of the departure of a major character, which changed the whole dynamic of the series, turning it into a different direction (Season 10 broadcasts Oct 6, 2019). For fans of the show, much of what is in this article is me stating the obvious. I know many people who have stopped watching the show after various seasons, for one reason or another. I also know people who have never watched TWD and never will, and some who have just started watching. There may be some hints and clues about certain things, but there are no real spoilers here. This article is about how the show affects me, personally.

Someone on Facebook commented that they stopped watching simply because the show is so sad, even depressing. True. This is not a comedy. There’s a lot of sorrow and sadness in almost every episode, a veritable trail of tears. Sometimes the grief on an actor’s face is enough to get to me. There are powerful emotions here: both love and hate, as well as fear and horror in the eyes of the characters; there’s also plenty of heart and soul poured into these scenes, which the cast so effectively conveys. As a relative told me when we were discussing the series over the Labor Day weekend, “My heart has been ripped out over and over again by what happens to these characters. I feel their pain, I feel their grief and I mourn with them.” I agree with her. I’ve gotten caught up in the lives and deaths of these characters. So please, bear with me.

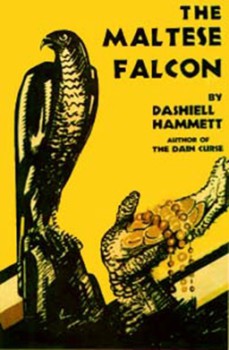

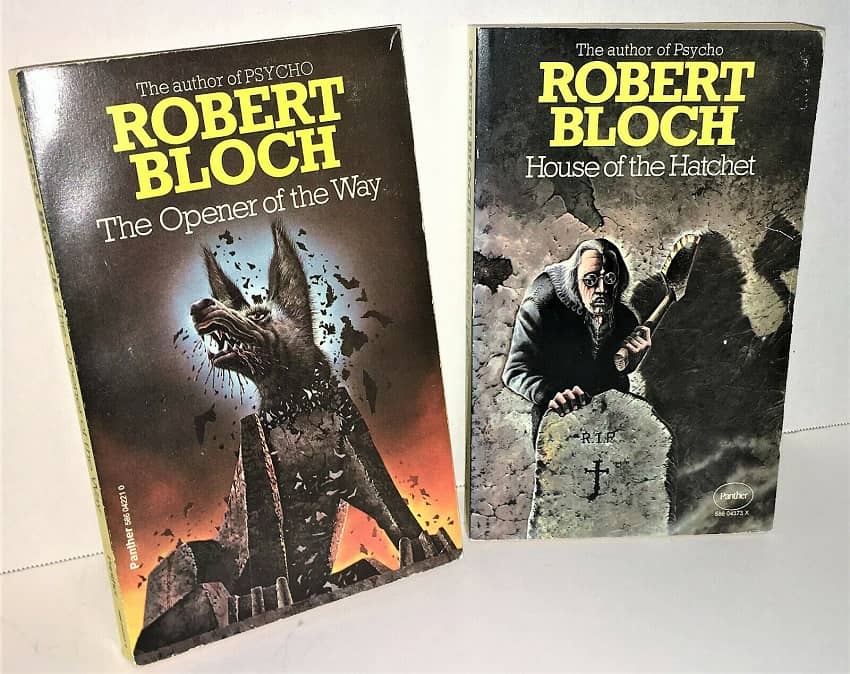

Although I’ve read only a handful of Robert Kirkman’s graphic novels, I’ve been a fan of the television series since episode one, and still remain a fan. I’m not a mad puppy because the show’s producers and writers made some changes which aren’t part of Kirkman’s mythos. Certain characters that had been killed in the graphic novels became so popular on the TV show that the producers decided to keep them around. Other popular characters were killed off on the show and, as most writers know, characters and plot twists often demand to be heard and made.

All in all, I think Frank Darabont, Gale Anne Hurd, Greg Nicotero, Howard Berger, and a truly outstanding ensemble cast all brings Kirkman’s vision to life. Yes, I get frustrated with the show over some plot twists, when the good guys fail to kill the bad guys when they had the chance, or when a likeable character is killed off. Yet such decisions often lead to more plot twists and turns. All that being said, the reality of TWD’s world reflects the true nature of Life: Death happens, tragically, senselessly, unexpectedly. Good people die. Bad people go on living. Even good decisions can lead to tragic and fatal results. Every decision, whether wise or foolish, has some sort of consequence. Sometimes the results are small blessings. Sometimes things go horribly wrong. Murphy’s Law rules in this world. Either you’re alive and fighting desperately to stay that way, or you’re dead — permanently or not. Everything means something. Everything ties into something else. The road to Hell is paved with good intentions and mortared with bad ones, and this is the world of The Walking Dead. This is Hell.

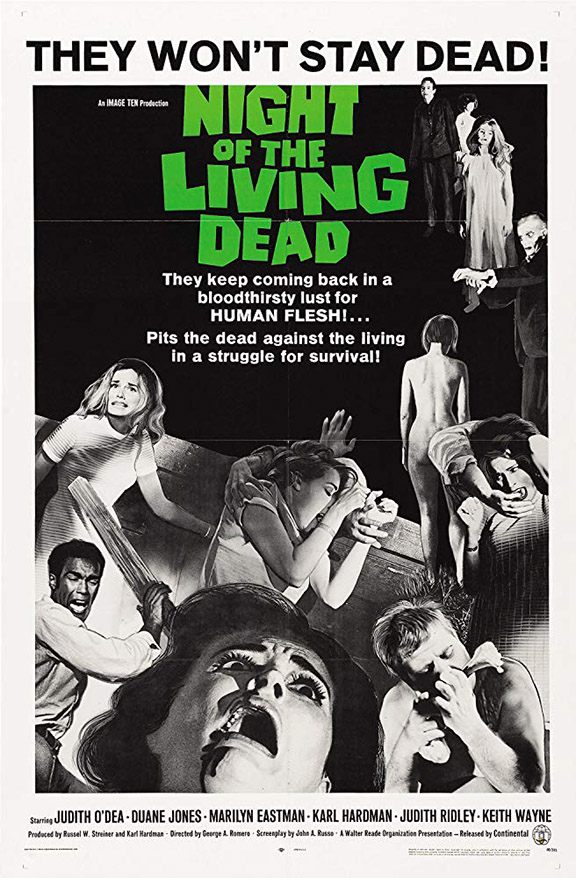

“When there’s no more room in Hell, the Dead shall walk the Earth.” — George A. Romero, Dawn of the Dead (original 1978)

TWD’s Ancestry

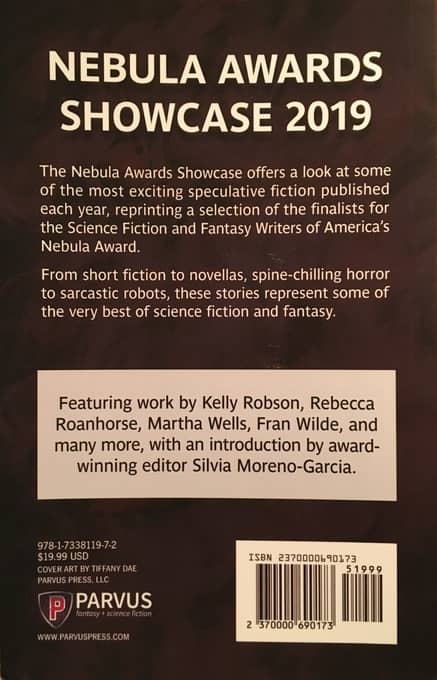

The Walking Dead is a direct and legitimate descendant of George Romero’s Living Dead films, and it often pays homage to him. For me, TWD is the penultimate “zombie apocalypse” epic, and like Romero’s films, the series is not about the zombies. Yes, the show is bloody and graphically violent, as it should be. But I see nothing gratuitous here; that’s the nature of this vicious world, and only part of the horror that has befallen it. The show is all about the people who fight for their lives, fighting to survive in a dark and hopeless world. You can replace the walking dead with more realistic threats like nuclear holocaust, a pandemic, world-wide drought and famine — whatever. It would still be much the same: a nightmare.

In a way, the series reminds me of the post-apocalyptic novels of J.G. Ballard: The Crystal Word, The Drought, The Wind from Nowhere, and The Drowning World. Ballard used ecological global disasters to examine the human condition, to tell stories about the survivors and how these catastrophes affect them, how they change them. This is what The Walking Dead is doing in the context of a zombie apocalypse, and why it still works for me. Although the show is played out in a scenario filled with terror and horror, it is not just another tale of zombies eating the flesh of the living: this is pure human drama, filled with tension and suspense, and yet not without subtle touches of humor that come from the dialog between characters who are not there just for comedic relief, nor does the humor play out through moments of slapstick involving comical zombies. The resurrected Dead in TWD, while slow-moving, are savage, dangerous and deadly, and there are a lot of them — hordes and herds of them all over the place. But the Dead are innocents, like any jungle or forest animal. No longer human, they do what they do, driven by mindless instinct: they eat anything that lives, although their main prey is people: we’re no longer at the top of the food chain. Ah, but people can be much worse: they terrorize other people and commit atrocities that far surpass what any zombie can do. Everything in life is about people, and everything about this show revolves around people, many of whom are just as dangerous as the living Dead. Sure, the Dead pose a threat because they outnumber us, they can multiply faster than we can, they’re relentless and they never get tired. As for the Living . . . they can think and plan, organize and shoot us from a distance. The Dead aren’t the monsters here: no . . . human beings are the monsters.

In essence, The Walking Dead is about human endurance and human frailty. The show is a celebration of the human spirit, and runs the entire spectrum of the human condition: finding and losing love; family, friendship and loyalty; trust and betrayal; heroism and cowardice; salvation, redemption, forgiveness; justice versus revenge; subjugation and slavery; kindness, depravity and barbarism. It’s about the capricious malevolence of greedy and power-hungry men and women: the strong prey on the weak. Through the characters that inhabit this world, the good, the bad and the ugly sides of human nature are revealed. We’re shown how an apocalypse of any kind will affect and change us. These characters have all lost someone they love and hold near and dear in their hearts. Many have lost everything they knew and had in life. The people in this world of the Dead are orphans of an apocalyptic storm, yet they hang on to what little hope they have. The Walking Dead is an End of the World scenario: dark and grim, brutal and cruel. To put a religious spin on it all, as George Romero often did . . . this could very well be the End Times, the Tribulation. This is Armageddon. But there’s no Rapture here, only the resurrection of the dead, and in the context of this show it’s the greatest cosmic joke of all.

The television series, like the graphic novels, is also about people who would never have met, if not for this apocalyptic nightmare. These people are fighting to survive, to protect each other from the Dead as well as from other people. Against all odds, they’re establishing communities and trying to rebuild civilization. They’re trying to save what’s left of the world. What this series does so well is to bring people together. Love blossoms, although lovers change, grow and move on — or are literally torn apart. There are gay, lesbian and interracial romances, and race, creed, color, religion and sexual orientation no longer matter to most of these characters. They’re just trying to rebuild their lives and find some happiness in a dying world inhabited by the Walking Dead. The world also has its share of human predators in the form of various gangs of killers, thieves and marauders: the butchers of Terminus, the Grady Memorial Hospital enclave and the murderous scavengers called the Wolves, for example.

Unlike the Resident Evil series, for instance, (which also owes much to George Romero), The Walking Dead is not wall-to-wall action, although it can hold its own when those moments burst upon the scene. Action scenes are expertly choreographed, filmed and edited. The special effects by KNB EFX are excellent. Make-up, practical effects, animatronic zombies, CGI, real locations, cinematography, set design and set decoration . . . these are all done with loving care and are as good as and often better than anything done in theatrical films. Everything about TWD is epic in scope, vision, characters and plot. However, all this would be mere window dressing if not for solid, three-dimensional characters, their motives and alliances, conflicts, suspicions and betrayals. The characters, their relationships, what they do, how they react, what they choose — these drive the plot and make the show interesting to me. Yeah, producers are making a big-budget zombie epic, and they pull none of their gory punches. They do it all. What they don’t do is neglect the human element, they don’t forget character development, which is always front and center, and a well-cast ensemble of fine actors bring to vivid life the characters they portray.

“They’re us. We’re them and they’re us.” — George Romero, Night of the Living Dead (1990 remake)

No “Red Shirts” Here

What I like are the quiet moments between the characters, revealing moments of reflection and discussion, when we learn more about them and come to understand them. Almost every major character has a back story, often told through flashback or dialog. Good guys or bad guys, we come to see this grave new world through their eyes. Each character is unique, although there are characters that serve as nothing more than “red shirts” — zombie fodder. The cast is superb, creating deep and complex characters: there are few clichés or stereotypes here. Characters have story arcs, and those with the most interesting and surprising arcs are my favorites. For instance: Morgan (Lennie James) — deeply troubled and conflicted, but heroic and honorable; he is the first character to save the life of Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln), the star of the series. Glenn (Steven Yuen) — likeable, young, brave, and who grows into a true leader: he is truly the one who sets the ball into play when he saves Rick from a herd of Walking Dead. That simple act of kindness takes them on a journey of friendship and a quest to build a safe haven for their group of survivors. I have many favorites: Herschel (the late Scott Wilson), Carol (Melissa McBride), Darryl (Norman Reedus), Michone (Danai Gurira), Eugene (Josh McDermitt), Tyrese (Chad Coleman), Sasha (Sonequa Martin-Green), Abraham (Michael Cudlitz), Rosita (Christian Serratos), Tara (Alanna Masterson), Maggie (Lauren Cohan), and Father Gabriel (Seth Gilliam.) It’s a huge cast, and the actors always get some memorable screen time in which their talent and acting skills allow them to shine. The cast is run through the mill and put through the whole gamut of human emotions and conflicts. Now I must mention the three villains who often steal the show, each one interesting, complicated, unique, and each quite different from the others.

![twd-4]() |

![redshirt]() |

First, we have the Governor of Woodbury, played with charming, disarming, creepy and ultimately deadly perfection by David Morrissey. A charismatic leader with a nasty agenda and a violent way of dealing with his enemies and traitors, for him there was no redemption. Then there’s Negan, leader of the self-styled Saviors of Sanctuary, expertly portrayed by Jeffrey Dean Morgan. He’s a likeable badass, but truly cruel; he commits acts of murder and mayhem that would make Satan cry out in horror. He’s my favorite, and his arc has taken an unexpected turn. Negan has to pay for his crimes, but I hope he dies saving the lives of others, thus winning some redemption for himself. MINOR SPOILER ALERT: he’s already risked his life to save someone, and that act of unselfish heroism could be a new beginning for him. (As I stated above, I’ve read only a handful of the graphic novels, so I have no idea what becomes of Negan and, of course, what the show’s producers and writers might do with him.) Now we have an eerie, sinister and disturbing villainess: Alpha — played to wicked perfection by Samantha Morton. She’s the leader of the Whisperers, a community of people who prefer to live in the wild and have come up with a clever but grisly way to survive and walk among the Dead. They are, in my opinion, the most dangerous threat to the communities of Alexandria, the Kingdom, Hilltop and Oceanside because not only are there a lot of them, and they just come out of nowhere, they’re using the Dead, whom they call their Guardians, as their own private army.

What I also like about the show is that there are few pop-culture references. No one yells out, “Shoot ‘em in the head, like in the movies!” There’s no mention of other cinematic genres, either. In episode one, policeman Rick Grimes tells his partner Shane that his brother was once stuck in a blizzard with only cake or snacks, and the audiotapes of The Lord of the Rings, and later someone calls him Clint Eastwood. Another character mentions the arrival of Maggie during a crucial scene, “like Zorro on a horse,” and one little girl is told to read Tom Sawyer. That’s pretty much it. These are timeless references, not references to current artists, films, musicians, actors, politicians and celebrities. The excellent soundtrack by Bear McCreary, while using an original score, also includes a few known and popular songs, which works for me because it adds an element of realism to the series.

I finished writing this article on September 8, 2019, and The Walking Dead won’t be entering its tenth season until October. I have avoided all fan pages, websites and even the official Facebook page because I don’t want to know what may or may not happen next. I have, however, heard that Robert Kirkman’s final novel in the series is on its way. I have not seen even one episode of Fear the Walking Dead, and I don’t know if I ever will. I’ve also heard that another spin-off is in the works, as well as a theatrical film starring one of the actors who left TWD, but not because he or she was killed off. Perhaps this is now getting out of hand and too much is a little too much. But I suppose as long as people keep watching and the cash cow can still be milked, the Dead will continue to walk. I’d like to see TWD end before it grows stale for me, as it already has for so many others. I can see the show taking two or three more seasons at most to reach a satisfactory conclusion, although it may take longer, depending on how closely the producers stick to Kirkman’s novels, how he ends his series, and how well the ratings hold up. As much as I love the characters, the plot twists and turns, I hope The Walking Dead doesn’t end up with worn-out feet and finish with an “and they all lived happily ever after” finale.

What, No “Zombies”?

A side note here: I have yet to hear the word zombie used in The Walking Dead. According to what I heard, the “Bible” the writers use states that the word not be used. I can’t remember if Kirkman ever used zombie in his graphic novels, but it seems to me that the series’ producers and writers don’t want to use a term that has been incorrectly used and overused in films and TV. It’s almost as if zombie is a word unknown to the characters of TWD’s world, and they have no zombie myths and legends, no zombie films. Thus, the Dead are commonly referred to as Walkers, although different communities have their own words for them: Biters and Skineaters, for example. I applaud that decision by all involved.

In Part II of this blog series (coming soon), I’ll give my thoughts on how a new definition of zombie crept into the lexicon and vocabulary of pop culture.

Joe Bonadonna is the author of the heroic fantasies Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser (winner of the 2017 Golden Book Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy); Mad Shadows II: Dorgo the Dowser and the Order of the Serpent; the space opera Three Against The Stars; the sword and planet space adventure, The MechMen of Canis-9; and the sword & sorcery adventure, Waters of Darkness, in collaboration with David C. Smith. With co-writer Erika M Szabo, he wrote Three Ghosts in a Black Pumpkin (winner of the 2017 Golden Books Judge’s Choice Award for Children’s Fantasy), and The Power of the Sapphire Wand. He also has stories appearing in: Azieran—Artifacts and Relics, GRIOTS 2: Sisters of the Spear, Heroika: Dragon Eaters, Poets in Hell, Doctors in Hell, Pirates in Hell, Lovers in Hell, and the upcoming Mystics in Hell; Sinbad: The New Voyages, Volume 4; and most recently, in collaboration with author Shebat Legion, he wrote Samuel Meant Well and the Little Black Cloud of the Apocalypse. In addition to his fiction, he has written a number of articles and book reviews for Black Gate online magazine.

Visit his Amazon Author or his Facebook Author’s page: Bonadonna’s Bookshelf

Joe Bonadonna has been a contributor to Black Gate since 2011, most recently posting his view on Dystopian Fiction:

IMHO: A Personal Look at Dystopian Fiction — Part One and IMHO: A Personal Look at Dystopian Fiction — Part Two: J.G. Ballard

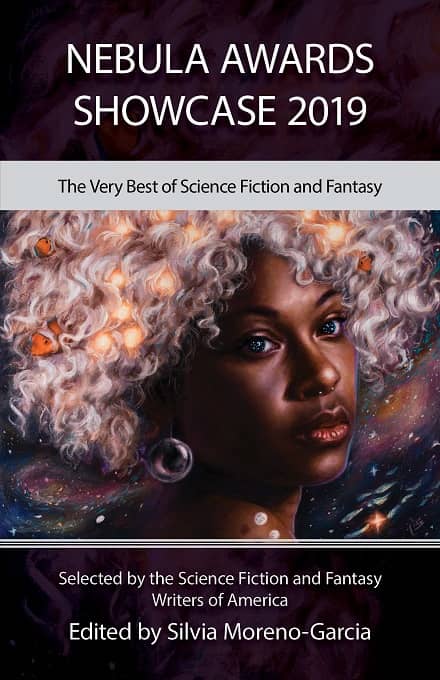

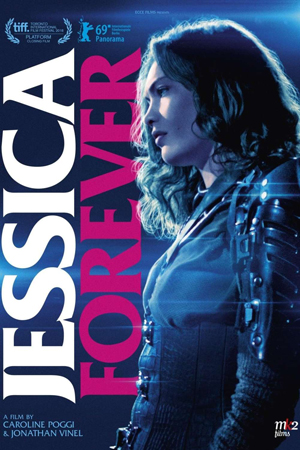

My first movie on July 30 was the first feature by two French directors of independent short films, Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel. Jessica Forever, which the duo wrote as well as directed, is set in a near future in which disaffected and violent youth, mostly male, roam empty suburbs. The law hunts them down with killer drones, and the movie opens with a cloud of drones after one man, Kevin (Eddy Suiveng), who has squatted in an empty house. He’s saved from the law by a mysterious woman named Jessica (Aomi Muyock) and her squad of young men, who welcome Kevin into the fold.

My first movie on July 30 was the first feature by two French directors of independent short films, Caroline Poggi and Jonathan Vinel. Jessica Forever, which the duo wrote as well as directed, is set in a near future in which disaffected and violent youth, mostly male, roam empty suburbs. The law hunts them down with killer drones, and the movie opens with a cloud of drones after one man, Kevin (Eddy Suiveng), who has squatted in an empty house. He’s saved from the law by a mysterious woman named Jessica (Aomi Muyock) and her squad of young men, who welcome Kevin into the fold. That’s a good idea that’s mostly played well, showing their limits as well their strengths, showing how they deal with loss and how the group deals with arguments among itself. And yet there’s a sense of something lacking. How these men got to be how they are is unclear, and how successful they are at building a new society is ultimately debateable. Jessica herself is an enigma, underplayed and underwritten to the point where virtually any meaning can be projected onto her. Is she Christ? Is she Peter Pan’s Wendy, or Pan himself? A Pied Piper? The ambiguity’s simply too overwhelming.

That’s a good idea that’s mostly played well, showing their limits as well their strengths, showing how they deal with loss and how the group deals with arguments among itself. And yet there’s a sense of something lacking. How these men got to be how they are is unclear, and how successful they are at building a new society is ultimately debateable. Jessica herself is an enigma, underplayed and underwritten to the point where virtually any meaning can be projected onto her. Is she Christ? Is she Peter Pan’s Wendy, or Pan himself? A Pied Piper? The ambiguity’s simply too overwhelming. Poggi and Vinel are part of a movement that has produced a document called the Incoherence Manifesto. Jessica Forever doesn’t always adhere to the rules of the manifesto, which may be appropriately incoherent. But I note Incoherent auteur Bertrand Mandico has said that “To be incoherent means to have faith in cinema, it means to have a romantic approach, unformatted, free, disturbed and dreamlike, cinegenic, an epic narration. Incoherence that’s an absence of cynicism but not irony.” And it’s quite possible to see a lot of this in Jessica Forever. Romantic, yes, dreamlike, certainly, cinegenic in the sense of attractive to viewers, yes. Arguably the story has moments of striving for epic. What may be most significant, though, is that there is a distinct absence of cynicism. There’s irony in the unfolding of the plot, but not a cynic’s sense of pointless or of the inherent corruption of humanity.

Poggi and Vinel are part of a movement that has produced a document called the Incoherence Manifesto. Jessica Forever doesn’t always adhere to the rules of the manifesto, which may be appropriately incoherent. But I note Incoherent auteur Bertrand Mandico has said that “To be incoherent means to have faith in cinema, it means to have a romantic approach, unformatted, free, disturbed and dreamlike, cinegenic, an epic narration. Incoherence that’s an absence of cynicism but not irony.” And it’s quite possible to see a lot of this in Jessica Forever. Romantic, yes, dreamlike, certainly, cinegenic in the sense of attractive to viewers, yes. Arguably the story has moments of striving for epic. What may be most significant, though, is that there is a distinct absence of cynicism. There’s irony in the unfolding of the plot, but not a cynic’s sense of pointless or of the inherent corruption of humanity.

I approached my second and last film of July 30 with real uncertainty. I’d never seen many tokusatsu films or TV shows, and what I had seen I hadn’t cared for. (‘Tokusatsu’ literally means something like ‘special effects,’ but in the West it’s come especially to refer to shows like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider.) Still, playing in the De Sève Cinema was Garo — Under the Moonbow (Garo: gekkô no tabibito, 牙狼 — 月虹ノ旅人, also translated Garo: Moonbow Traveler), written and directed by Keita Amemiya. It’s the latest installment of a franchise, created by Amemiya, which began with a 2005 TV series and has continued through more TV shows, live-action movies, and anime series. as well as video games, manga, and various other tie-ins. A veteran creator of tokusatsu dramas, Amemiya is particularly known for his powerful design sense, and the images and description of the film promised a stylish fantasy adventure. Although it’d be my first experience with a series that had dozens of hours of continuity behind it, I decided it was worth passing up a chance to see The Crow on the big screen in order to watch Under the Moonbow.

I approached my second and last film of July 30 with real uncertainty. I’d never seen many tokusatsu films or TV shows, and what I had seen I hadn’t cared for. (‘Tokusatsu’ literally means something like ‘special effects,’ but in the West it’s come especially to refer to shows like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider.) Still, playing in the De Sève Cinema was Garo — Under the Moonbow (Garo: gekkô no tabibito, 牙狼 — 月虹ノ旅人, also translated Garo: Moonbow Traveler), written and directed by Keita Amemiya. It’s the latest installment of a franchise, created by Amemiya, which began with a 2005 TV series and has continued through more TV shows, live-action movies, and anime series. as well as video games, manga, and various other tie-ins. A veteran creator of tokusatsu dramas, Amemiya is particularly known for his powerful design sense, and the images and description of the film promised a stylish fantasy adventure. Although it’d be my first experience with a series that had dozens of hours of continuity behind it, I decided it was worth passing up a chance to see The Crow on the big screen in order to watch Under the Moonbow. It is not flawless. The lighting in particular feels like a TV show, and not a particularly ambitious one (though in fairness this movie is a direct sequel to one TV series in particular, so it may simply be following a pre-existing look). The acting’s very flat, which fits with the characters — Moonbow has the surface quality of a pulp potboiler or a fairy tale, both of which the story vaguely recalls at different times. There is certainly a highly stylised presentation of character, to an extent in the writing but definitely in the performances; the way poses are struck, the way reactions are exaggerated. It’s clear, and not overdone to the point of self-parody, but is self-consciously theatrical if not broad.

It is not flawless. The lighting in particular feels like a TV show, and not a particularly ambitious one (though in fairness this movie is a direct sequel to one TV series in particular, so it may simply be following a pre-existing look). The acting’s very flat, which fits with the characters — Moonbow has the surface quality of a pulp potboiler or a fairy tale, both of which the story vaguely recalls at different times. There is certainly a highly stylised presentation of character, to an extent in the writing but definitely in the performances; the way poses are struck, the way reactions are exaggerated. It’s clear, and not overdone to the point of self-parody, but is self-consciously theatrical if not broad.

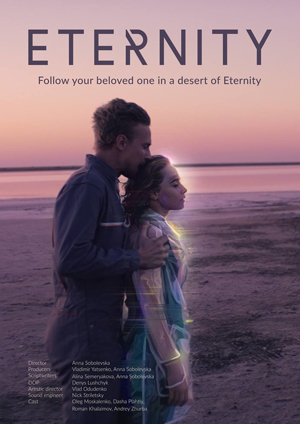

After taking a day to attend to various non-cinema matters, I came early to the last day of the Fantasia Film Festival. I had two movies I wanted to see in theatres, but first I wanted to catch up on something I’d missed when played on the big screen: the 2019 International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase. Luckily, I was able to watch it at the Fantasia screening room. Uncharacteristically, American shorts dominated this year; in an appropriately science-fictional statistic, 7 of 9 movies were from the US, with one from Australia that ended the showcase (at least in the order described in the Fantasia program) and one from Ukraine that began it.

After taking a day to attend to various non-cinema matters, I came early to the last day of the Fantasia Film Festival. I had two movies I wanted to see in theatres, but first I wanted to catch up on something I’d missed when played on the big screen: the 2019 International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase. Luckily, I was able to watch it at the Fantasia screening room. Uncharacteristically, American shorts dominated this year; in an appropriately science-fictional statistic, 7 of 9 movies were from the US, with one from Australia that ended the showcase (at least in the order described in the Fantasia program) and one from Ukraine that began it. Next came “Here & Beyond,” a 17-minute piece directed by Colin West from a script he wrote with Corey Aumiller. Mac (Greg Lucey) used to be a kids’ tv-show personality, presenting science facts as part of a duo with his dead wife Ruth (Christine Kellogg-Darrin). Now his brain is degenerating. As he forges a strange friendship with cynical teen neighbour Tess (Laurel Porter), he must strip away everything from his home that reminds him of his wife, in order to minimise confusion; but does he have a way to change the flow of time?

Next came “Here & Beyond,” a 17-minute piece directed by Colin West from a script he wrote with Corey Aumiller. Mac (Greg Lucey) used to be a kids’ tv-show personality, presenting science facts as part of a duo with his dead wife Ruth (Christine Kellogg-Darrin). Now his brain is degenerating. As he forges a strange friendship with cynical teen neighbour Tess (Laurel Porter), he must strip away everything from his home that reminds him of his wife, in order to minimise confusion; but does he have a way to change the flow of time? “The Slows” is a 22-minute adaptation of

“The Slows” is a 22-minute adaptation of  It’s hard not to think of The Good Place given the way this film begins. Luckily the dialogue between Ava and the computer is witty enough to sustain the impression, though the ending’s downbeat, and so produces a different tone. The film takes place in one location, with one visible actor, and makes the idea work.

It’s hard not to think of The Good Place given the way this film begins. Luckily the dialogue between Ava and the computer is witty enough to sustain the impression, though the ending’s downbeat, and so produces a different tone. The film takes place in one location, with one visible actor, and makes the idea work. Next came one of the most frightening movies of the festival, for reasons that had nothing to do with plot. “Face Swap” was written and directed by the duo of David Gidali and Einat Tubi. In the near future, a man (Troy Caylak) has convinced his wife (Megan Gray) to go to a futuristic love hotel where holographic projectors will allow two guests to take on the images of chosen celebrities through real-time animation. He becomes George Clooney, she becomes Rachel McAdams. But there’s a twist he doesn’t expect. It’s solidly-made, with a kind of modern update on a very old low-comedy trick.

Next came one of the most frightening movies of the festival, for reasons that had nothing to do with plot. “Face Swap” was written and directed by the duo of David Gidali and Einat Tubi. In the near future, a man (Troy Caylak) has convinced his wife (Megan Gray) to go to a futuristic love hotel where holographic projectors will allow two guests to take on the images of chosen celebrities through real-time animation. He becomes George Clooney, she becomes Rachel McAdams. But there’s a twist he doesn’t expect. It’s solidly-made, with a kind of modern update on a very old low-comedy trick.  Kit Zauhar wrote and directed the 15-minute “The Terrestrials.” In the future, there is a device that allows two people to have sex without bodies, in a kind of cyberspace; it’s Tinder without matter. Lucy (Arabella Oz), a reserved scientist with an interest in the search for extraterrestrial life, has sex with a stranger named Will (Henry Fulton Winship). Then there are technical issues, and Lucy has to reach out in ways she didn’t expect. The characters have some thought behind them and the ending’s very strong, while the theme of a search for connection is echoed by the science-fictional idea of the movie.

Kit Zauhar wrote and directed the 15-minute “The Terrestrials.” In the future, there is a device that allows two people to have sex without bodies, in a kind of cyberspace; it’s Tinder without matter. Lucy (Arabella Oz), a reserved scientist with an interest in the search for extraterrestrial life, has sex with a stranger named Will (Henry Fulton Winship). Then there are technical issues, and Lucy has to reach out in ways she didn’t expect. The characters have some thought behind them and the ending’s very strong, while the theme of a search for connection is echoed by the science-fictional idea of the movie. This is a clever film, with an intricate yet character-oriented reason behind its initial scene. There are some developments that threaten to send the story spinning off in weird directions; there may be too many ideas here for a single short. But Maxine’s an engaging lead, and her offhand discussions about the various people she’s met and things she’s done are lovely. (As when she mentions meeting Steven Spielberg in multiple incarnations: “Nice guy. Keeps trying to make 1941 happen.”) It moves sharply, and shifts registers smoothly to incorporate a surprising amount of violence.

This is a clever film, with an intricate yet character-oriented reason behind its initial scene. There are some developments that threaten to send the story spinning off in weird directions; there may be too many ideas here for a single short. But Maxine’s an engaging lead, and her offhand discussions about the various people she’s met and things she’s done are lovely. (As when she mentions meeting Steven Spielberg in multiple incarnations: “Nice guy. Keeps trying to make 1941 happen.”) It moves sharply, and shifts registers smoothly to incorporate a surprising amount of violence. It’s a well-acted piece, but I found the two ideas (cannibalism from food shortage, and a new kind of dementia) seemed excessive in one story. The world feels like it hasn’t changed enough for widespread cannibalism to be believable — if there are food shortages so intense cannibalism becomes a logical solution there must be profound changes in society, but the movie looks much like the present day. Meanwhile, the Hebedus virus feels like a convenient way to tell a story about dementia without actually writing about a specific condition. There are a couple of good ideas here (for example, the human meat is given a code, so consumers can avoid a specific code of meat and be sure they’re not eating a member of their family) and the film’s extremely well-acted, particularly on the part of McNeill, who gets a lot across by merely staring vacantly in front of him. It’s not a bad movie, but I found it unengaging.

It’s a well-acted piece, but I found the two ideas (cannibalism from food shortage, and a new kind of dementia) seemed excessive in one story. The world feels like it hasn’t changed enough for widespread cannibalism to be believable — if there are food shortages so intense cannibalism becomes a logical solution there must be profound changes in society, but the movie looks much like the present day. Meanwhile, the Hebedus virus feels like a convenient way to tell a story about dementia without actually writing about a specific condition. There are a couple of good ideas here (for example, the human meat is given a code, so consumers can avoid a specific code of meat and be sure they’re not eating a member of their family) and the film’s extremely well-acted, particularly on the part of McNeill, who gets a lot across by merely staring vacantly in front of him. It’s not a bad movie, but I found it unengaging.

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up.

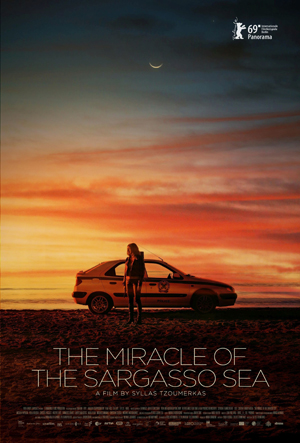

The nice thing about my last day of Fantasia was that rather than sit in one place, I would watch something on my own in the screening room, then something at the small De Sève Cinema, and finally something at the big Hall Theatre. It had the well-rounded feeling of a good summing-up. I will note that I have seen other reviews that have a different assessment. Generally writers who saw more strangeness in the film had more of an appreciation for it. To me, the dream sequences and religious visions felt peripheral in terms of story structure and, to a large extent, character. They’re part of a symbolic picture, and the movie is at least engaged in trying to present a complexity of theme and image — the title, for example, is a reference to the life-cycle of eels, who migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. I felt these ideas were interesting, but did not add to the drama of the picture, while the drama itself did not add to their depth. In other words, the film remained basically realistic to me. If you as a viewer find more strangeness in it, you’ll probably have a higher opinion of it.

I will note that I have seen other reviews that have a different assessment. Generally writers who saw more strangeness in the film had more of an appreciation for it. To me, the dream sequences and religious visions felt peripheral in terms of story structure and, to a large extent, character. They’re part of a symbolic picture, and the movie is at least engaged in trying to present a complexity of theme and image — the title, for example, is a reference to the life-cycle of eels, who migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. I felt these ideas were interesting, but did not add to the drama of the picture, while the drama itself did not add to their depth. In other words, the film remained basically realistic to me. If you as a viewer find more strangeness in it, you’ll probably have a higher opinion of it. The problem is that the film never finds a strong enough dramatic spark. For too long the movie’s a slice-of-life drama that splits its focus. Interesting ideas about character never quite develop. A situation’s established, and then is not explored so much as reiterated. Even the symbolic dimension, although extremely well-machined, doesn’t give the action the resonance it should. By the end, the lack of drama undercuts that symbol-structure and the film’s themes: the implication of society in the crimes of some of its most prominent members is attenuated. Oddly, because the characters are set up so well as individuals, they do not speak to structural societal issues. They seem to do what they do because of who they are, as opposed to being who they are because of the way the world made them.

The problem is that the film never finds a strong enough dramatic spark. For too long the movie’s a slice-of-life drama that splits its focus. Interesting ideas about character never quite develop. A situation’s established, and then is not explored so much as reiterated. Even the symbolic dimension, although extremely well-machined, doesn’t give the action the resonance it should. By the end, the lack of drama undercuts that symbol-structure and the film’s themes: the implication of society in the crimes of some of its most prominent members is attenuated. Oddly, because the characters are set up so well as individuals, they do not speak to structural societal issues. They seem to do what they do because of who they are, as opposed to being who they are because of the way the world made them.

![1929-12-07 Fremont [OH] News-Messenger 8 Buck Rogers televox](http://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/1929-12-07-Fremont-OH-News-Messenger-8-Buck-Rogers-televox.jpg)

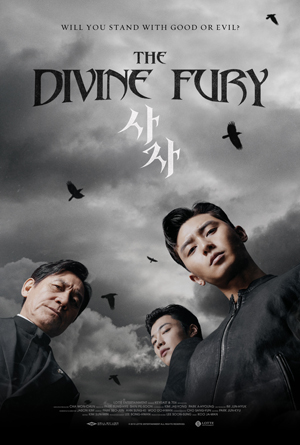

All good things must come to an end, they say, and for me Fantasia 2019 ended at the Hall Theatre with the Korean action-horror movie The Divine Fury (사자, romanised as Saja, literally Emissary). Directed by Kim Joo-hwan, it follows Yong-hu (Park Seo-jun), a champion MMA fighter who lost his father under mysterious circumstances at a young age. In the present, when mysterious wounds appear on his hands and he is attacked by a demonic force, a blind shaman guides him to exorcist Father Ahn (Ahn Sung-ki), who tells him the wounds are stigmata and give him great power in fighting demons. The two team up, reluctantly on the part of Yong-hu, who holds a grudge against Christianity after the death of his father. But there are dark forces at work in Seoul, and Yong-hu must use all his skills to defeat the forces of hell on earth.

All good things must come to an end, they say, and for me Fantasia 2019 ended at the Hall Theatre with the Korean action-horror movie The Divine Fury (사자, romanised as Saja, literally Emissary). Directed by Kim Joo-hwan, it follows Yong-hu (Park Seo-jun), a champion MMA fighter who lost his father under mysterious circumstances at a young age. In the present, when mysterious wounds appear on his hands and he is attacked by a demonic force, a blind shaman guides him to exorcist Father Ahn (Ahn Sung-ki), who tells him the wounds are stigmata and give him great power in fighting demons. The two team up, reluctantly on the part of Yong-hu, who holds a grudge against Christianity after the death of his father. But there are dark forces at work in Seoul, and Yong-hu must use all his skills to defeat the forces of hell on earth. So much for the action. As a horror movie The Divine Fury has a little bit more to say. The imagery recalls some of the classic American horror films; two exorcists struggling against a demon that’s possessed a young woman in her mother’s home can’t help but be a little familiar, and there is a sense that the movie’s not only conscious of its homage, but is in fact drawing some energy from being in dialogue with its predecessors. The mechanism of possession and the struggle of Father Ahn against demons is well drawn; Ahn seems to live in a series of hotel rooms, wandering the world at the behest of the Vatican, battling Satanic agents. The movie does a good job of showing us just enough of his life, and just enough of the struggle he’s engaged in. We know enough to be horrified, but not enough for the horror to turn into mere plot mechanics.

So much for the action. As a horror movie The Divine Fury has a little bit more to say. The imagery recalls some of the classic American horror films; two exorcists struggling against a demon that’s possessed a young woman in her mother’s home can’t help but be a little familiar, and there is a sense that the movie’s not only conscious of its homage, but is in fact drawing some energy from being in dialogue with its predecessors. The mechanism of possession and the struggle of Father Ahn against demons is well drawn; Ahn seems to live in a series of hotel rooms, wandering the world at the behest of the Vatican, battling Satanic agents. The movie does a good job of showing us just enough of his life, and just enough of the struggle he’s engaged in. We know enough to be horrified, but not enough for the horror to turn into mere plot mechanics. So it is here. Yong-hu’s a solid enough character, but doesn’t grow much through the film; on his own, he’s not really engaging enough to hold one’s attention for two hours and change. Ahn is more interesting, with a certain gravitas and world-weariness. It may not be surprising that his part of the story is more dramatically engaging. And there is a certain energy that comes when the two characters interact, as the life of a down-at-heels exorcist runs into the glitzy world of a martial-arts champion.

So it is here. Yong-hu’s a solid enough character, but doesn’t grow much through the film; on his own, he’s not really engaging enough to hold one’s attention for two hours and change. Ahn is more interesting, with a certain gravitas and world-weariness. It may not be surprising that his part of the story is more dramatically engaging. And there is a certain energy that comes when the two characters interact, as the life of a down-at-heels exorcist runs into the glitzy world of a martial-arts champion.

Yesterday I posted my last full review of a film from the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival. Today, then, a post looking back at this year’s Fantasia. First, as always, my profound thanks to everyone who puts the festival together. And thanks as well to the audiences, who give the festival a reason for being. Special thanks to everyone I watched movies with, everyone I waited in line with, and everyone who I talked with and hung out with during Fantasia 2019.

Yesterday I posted my last full review of a film from the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival. Today, then, a post looking back at this year’s Fantasia. First, as always, my profound thanks to everyone who puts the festival together. And thanks as well to the audiences, who give the festival a reason for being. Special thanks to everyone I watched movies with, everyone I waited in line with, and everyone who I talked with and hung out with during Fantasia 2019. In particular: Vladislav Bairamgulov’s folklore-like “A Little Light,” about a boy seeking fire in a deep wood, is atmospheric and funny. Park Sae-mi’s “Mira” is a wildly inventive expressionistic fable. Fillip Diviak and Zuzana Cupová’s “Cloudy” marries a sharp sense of humour with a strong design sense. Nicolas Deveaux’s “Athleticus” series of shorts is a uses straight-faced CGI to hilarious effect in showing animals competing in Olympic events. Thanh-Long Vo’s “Morpho Bleu” used a beautiful visual symbol to tell a fable about a young girl daring to learn new things, and did so without dialogue and in only one minute; it’s a splendid example of the power of visual storytelling.

In particular: Vladislav Bairamgulov’s folklore-like “A Little Light,” about a boy seeking fire in a deep wood, is atmospheric and funny. Park Sae-mi’s “Mira” is a wildly inventive expressionistic fable. Fillip Diviak and Zuzana Cupová’s “Cloudy” marries a sharp sense of humour with a strong design sense. Nicolas Deveaux’s “Athleticus” series of shorts is a uses straight-faced CGI to hilarious effect in showing animals competing in Olympic events. Thanh-Long Vo’s “Morpho Bleu” used a beautiful visual symbol to tell a fable about a young girl daring to learn new things, and did so without dialogue and in only one minute; it’s a splendid example of the power of visual storytelling.  I saw “Balloon” not too long after seeing the disappointing

I saw “Balloon” not too long after seeing the disappointing  It’s one of the virtues of the film festival format: the chance to see some of the best shorts of the year. Whether in showcases, or placed before a feature film, attending Fantasia means getting to see short works I would not get to see otherwise. Would not even have heard of, in fact.

It’s one of the virtues of the film festival format: the chance to see some of the best shorts of the year. Whether in showcases, or placed before a feature film, attending Fantasia means getting to see short works I would not get to see otherwise. Would not even have heard of, in fact.