![HBH_Murder]()

OK: The kidney stone passed and I spent last week trying to dig myself out of…well, everything! So, it’s another repeat colum this week. I happen to think this the best thing I ever wrote before I joined Black Gate. Yeah – you’re actually getting my good stuff here at Black Gate. Sad, ain’t it?

I wrote this for Sherlock Magazine, where I wrote a column reviewing mystery websites. Then-editor David Stuart Davies (a notable writer of Sherlock Holmes stories and non-fiction) let me write a feature. I will probably revisit this some day, as I’ve learned a lot more about hardboiled since then; but I still think this is pretty darn good. Let me know what you think!

And we’ll be back on track next week.

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

By now, readers of this column (all three of you) know that I’m ‘all-in’ on Sherlock Holmes and Solar Pons. But I am also a long-time hard boiled fiction afficionado. I’ve got a section of the bookshelves well-stocked with private eye/police novels and short stories, from Hammett and Daly to Stone and Burke.

Now, I wouldn’t bet my house on the premise of the following essay, which first appeared in Sherlock Magazine back when I was a columnist for that fine, now defunct periodical. But I believe that I make a more compelling argument than you thought possible at first glance. The roots of the American hard boiled school can be seen in Sherlock Holmes and the Victorian Era. Yes, really.

And if any of the hard boiled heroes mentioned catch your fancy, leave a comment. I’ll be glad to tell you more about them. Without further ado, I bring you “Hard Boiled Holmes.”

“But down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.”

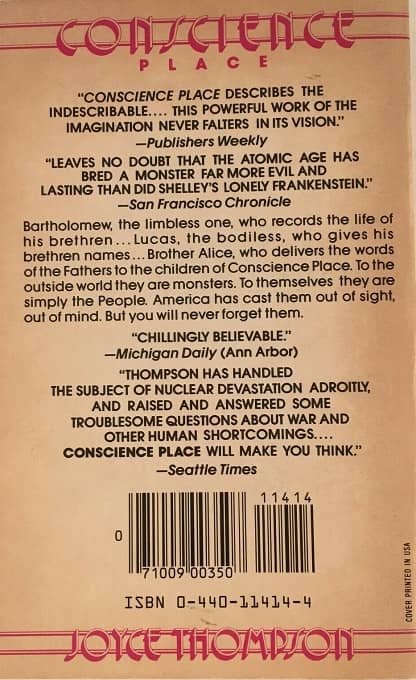

Raymond Chandler wrote these words in his essay, ‘The Simple Art of Murder.’ Ever since, the term ‘mean streets’ has been associated with the hard-boiled genre. One thinks of tough private eyes with guns, bottles, and beautiful dames. But was it really Chandler who created those words to describe the environment that the classic Philip Marlowe operated in?

Is it possible that it was Victorian London that gave birth to the mean streets, which would later become famous as the settings in the pages of Black Mask? Could it be that Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe were followers in the footsteps of Sherlock Holmes?

![HBH_Mask]() The era of detective fiction between the two World Wars is known as the Golden Age. This was the time of the country cozy and the locked-room mystery. Closed settings and high society were staples of the style, exemplified by Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr and Dorothy Sayers.

The era of detective fiction between the two World Wars is known as the Golden Age. This was the time of the country cozy and the locked-room mystery. Closed settings and high society were staples of the style, exemplified by Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr and Dorothy Sayers.

In America in the twenties, a counter to the Golden Age developed. Carroll John Daly, Frederick Nebel and Raoul Whitfield, among others, wrote ‘hard-boiled’ detective stories for Black Mask magazine. The two schools were reflections of conditions in England and America. The quaint country manor, never really an American setting, had little relevance to a United States economically booming after World War I, yet entangled in Prohibition.

The rise of the American gangster and the big city lifestyle lent itself to tough-talking, fast-shooting detectives in the Roaring Twenties (an era colorfully described by twenties New York City newspaperman Stanley Walker in The Night Club Era). The hard-boiled school was writing from the day’s news.

Dashiell Hammett, the first great hard-boiled author, said that all of his characters were based on real people he’d come across as a Pinkerton operative. The hard-boiled school and the Golden Age detective mysteries are very different. But what about the generation once removed: what about the Sherlock Holmes era?

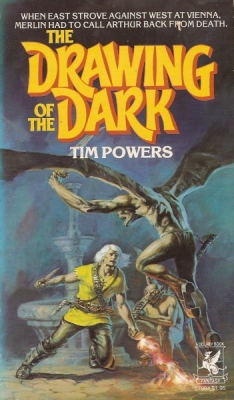

Arthur Morrison is remembered (when he is remembered at all) as the creator of Martin Hewitt, the private detective who replaced Sherlock Holmes in The Strand when Doyle sent our hero over a cliff at the Reichenbach Falls. Before that, in 1893, Morrison wrote a series of fourteen short stories that were published in The National Observer and released in book form as Tales of Mean Streets.

![HBH_Hewitt]()

Famed Holmes illustrator Sidney Paget also drew Martin Hewitt.

They were the depressing stories of the desperate people in London’s East End. These were the same streets that noted wilderness author Jack London would write about in The People of the Abyss. London went to the East End in the summer of 1902 and lived amongst the poorest of English society. Talk about delving into your subject matter!

The bleakness and utter despair of such an environment often resulted in crime and depravity. Dorset Street, well known among Ripperologists, was considered to be the most crime-riddled street in the entire city. In 1888, an estimated 1,500 people lived on the one hundred-and-fifty foot long street. It was said that the police were afraid to enter it after dark, and certainly did not go in alone. The seedy streets of Victorian London were a far cry from the halls and manors that Holmes often visited.

We know that Holmes frequently moved about the upper class, but he also often disguised himself as a workingman or other commoner for an investigation. The Canon is replete with instances of Watson being fooled by one of Holmes’ disguises. Even ‘The Woman,’ Irene Adler, was taken in not once, but twice, by Holmes’ theatrical abilities during “A Scandal in Bohemia” (although he gave himself away the second time).

Holmes was not simply a problem-solver for the rich. He investigated cases among the middle and lower classes as well. And some of those affairs took him to the rougher side of London. He traversed those mean streets that Morrison had written of.

Holmes certainly ventured to country houses and rural villages to solve crimes. The Hound of the Baskervilles, “The Boscombe Valley Mystery,” “The Sussex Vampire” and “The Solitary Cyclist” are just a few examples. But he was very much an urban sleuth. And Holmes-era writers helped paint a picture of the more dangerous side of England’s greatest city.

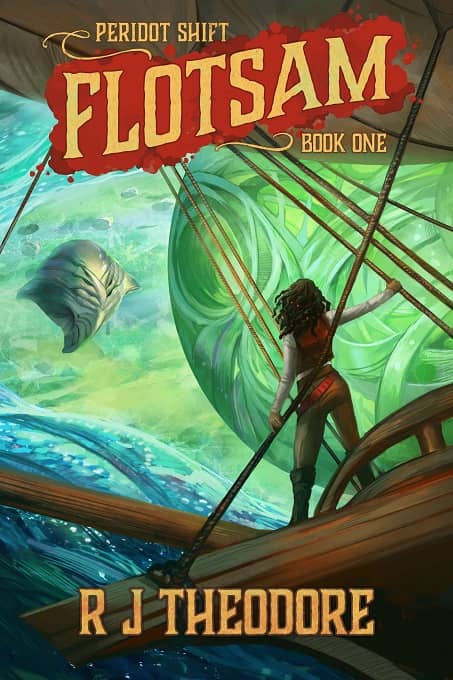

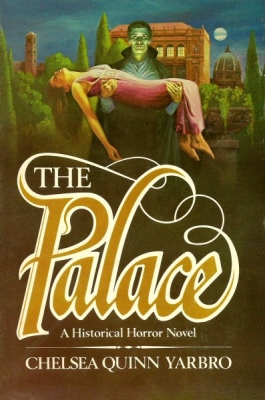

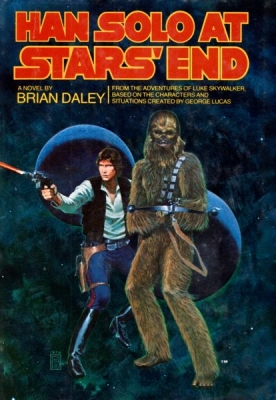

![HBH_Dain]()

James Coburn played a very Hammett-like Continental Op here.

However, the mean streets of hard-boiled stories were more than just the physical environments that they were in Holmes’ time. Many of the authors were writing about the good and evil in mankind, not just the roads and towns that the detectives found themselves in. Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op books are very much about the fundamental issues of morality and humanity, and the streets that he traveled extended to the criminals he pursued. The mean streets of The Dain Curse are more about the diabolical Owen Fitzstephan than the thoroughfares of San Francisco.

In “The Norwood Builder,” a successful businessman arranges a frame job, making it appear that his body was found in the remains of a building fire. It is not difficult to picture Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer encountering a similar situation as he investigates a southern California tycoon. The literal Victorian-era mean streets were redefined and reshaped for the new heard-boiled era. But the concept was already there in Doyle’s stories.

No one is going to confuse Victorian London with Hammett’s Poisonville. But the back alleys and opium dens of Doyle’s stories sometimes come to mind when reading Chester Himes’ excellent tales set in Harlem. Raymond Chandler popularly coined the phrase created by Arthur Morrison and transplanted it across one ocean and several decades. Doyle’s mysteries were primarily about Holmes and the crime itself. The best hard-boiled mysteries had deeper themes in their plots. The mean streets of Morrison were not simply copied, they were turned into something more.

But what about Sherlock Holmes and Sam Spade? Even a cursory glance shows us that the hard-boiled and Golden Age schools of mystery fiction were dissimilar. Were those characteristics that were so well developed by the American pulp writers of the twenties and thirties present in Doyle’s stories of the great detective?

Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple seemed to find more crime in the village of St. Mary Meade then existed in the entirety of London. It’s hard to believe how much malice and mayhem there was in the place. It simply wasn’t realistic. That element of realism, a key characteristic in the hard-boiled school, had more in common with Doyle’s tales.

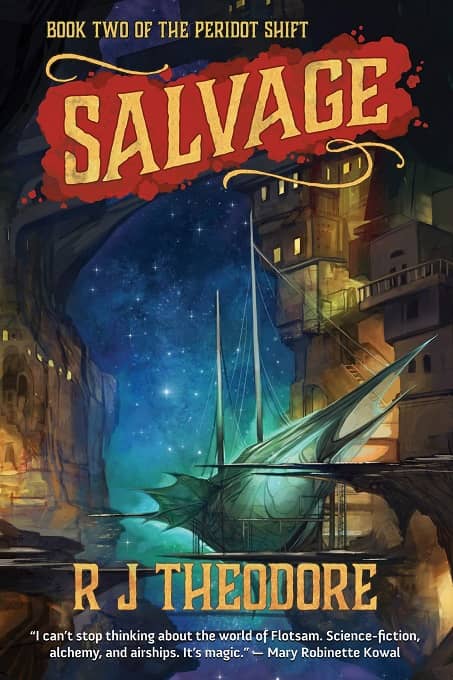

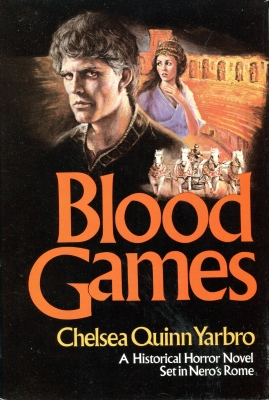

![HBH_VAlley]() Sure, there were the fantastic stories. Can you see a hard-boiled version of “The Devil’s Foot?” Didn’t think so. The ‘wax figure of Holmes’ ruse from “The Mazarin Stone” would not fly in a Paul Cain short story. But several of the Holmes stories had elements that could be read in the day’s headlines.

Sure, there were the fantastic stories. Can you see a hard-boiled version of “The Devil’s Foot?” Didn’t think so. The ‘wax figure of Holmes’ ruse from “The Mazarin Stone” would not fly in a Paul Cain short story. But several of the Holmes stories had elements that could be read in the day’s headlines.

Perhaps a bit factually stilted, The Valley of Fear had a very real basis in the story of James McParland (Birdy Edwards) and Pennsylvania’s Molly Maguires (The Scowrers). The Five Orange Pips incorporated the Ku Klux Klan. Anyone familiar with the case of Hawley Crippen, ‘The Mild Mannered Murderer,’ can see elements that appeared in Doyle’s “The Retired Colourman.”

Holmes’ competition, the private detective only identified as “Barker,” shadows Josiah Amberley in that story. Hammett’s Continental Op did a great deal of tailing suspects, just as the Pinkerton agent-turned-author himself did.

Another very important element of hard-boiled fiction was that of a “personal code of honor.” Sam Spade sums it up at the end of The Maltese Falcon when he turns in Brigid O’Shaughnessy. Near the end of a speech where he explains why he can’t let her go, he says “I won’t because all of me wants to – wants to say to hell with the consequences and do it..” It is the perfect example of the knight-errant putting ‘the code’ before his own interests.

Conan Doyle was certainly a proper British gentleman whose patriotic loyalties we see reflected in Watson. The author instilled his sense of personal honor into Holmes. Quotes are sprinkled throughout the Canon that reflect Holmes’ code of conscience over the dictates of law. A few examples:

I had rather play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience (“The Abbey Grange”)

I suppose that I am commuting a felony, but it is just possible that I am saving a soul (“The Blue Carbuncle”)

I suppose I shall have to commute a felony as usual (“The Three Gables”)

Legally, we are putting ourselves hopelessly in the wrong, but I think that it is worth it (“The Yellow Face”)

That first quote is a very representative look at Holmes’ attitude towards his personal code. In “Charles Augustus Milverton,” one could argue that Holmes aided in the murder of ‘the worst man in London.’ He does not put the law, or even legal justice, before what he believes is right.

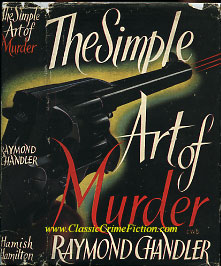

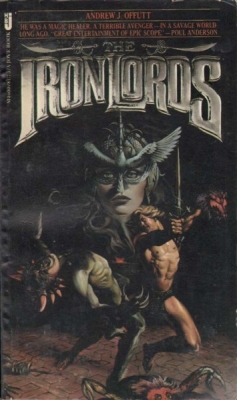

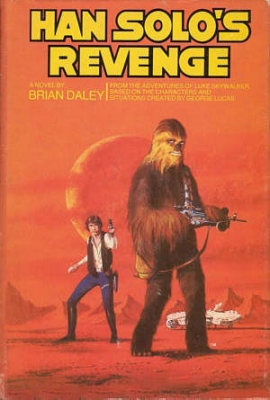

![HBH_Indemnity]()

A superb film. Not ‘My Three Sons’ Fred MacMurray!

This code was not a mandatory element of hard-boiled/noir writing. Jim Thompson’s gritty looks at American life didn’t usually feature detectives, and it’s often hard to find a code of honor when you can’t even locate a sympathetic person in the cast of characters. And James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice are almost bereft of moral conviction. But the code is important to the hard-boiled detective.

John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee carried on this code in a series of successful novels over twenty years. MacDonald’s favorite image of McGee, an unofficial private eye, was as a weary knight riding a worn-out steed, jousting with a broken lance. Travis McGee, perhaps as much as any detective from the pulps, personified the detective’s personal code of honor.

McGee differs from Holmes in this regard in that he was a much more humanized version of the character. But the elements of Holmes’ sense of personal right and wrong carried through the entire hard-boiled genre and on to its pulp private detective descendents. The hard-boiled hero was a man of honor, just as Holmes was decades before.

Rex Stout’s books starring Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin featured strong elements of the golden age and hardboiled schools. Goodwin was the tough-guy private eye who refused to compromise his code of ethics, frequently quitting when he felt his honor demanded it (though rarely even leaving the room before Wolfe agrees to placate him and Goodwin resumes work).

Black Mask was for the hard-boiled school what The Strand had been for Sherlock Holmes and the British mystery school. The mean streets of Holmes’ London had counterparts in the urban and moral settings of Hammett and Chandler. Doyle used real-world events in his plotting, the same way the American hard-boiled authors tore the headlines out of the daily papers and shaped them into action-packed tales.

Though not a direct model, Sherlock Holmes was a Victorian-era predecessor of Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe. Since we started with a quote from Chandler’s essay, we’ll finish with one as well: “…and Sherlock Holmes after all is mostly an attitude and a few dozen lines of unforgettable dialogue.” It’s a fitting epithet for Raymond Chandler’s own hard-boiled detective.

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Will Murray on Doc Savage

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: A Man Called Spade

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #3

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #4

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #5

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

A (Black) Gat in Hand: Back Deck Pulp #6

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: The Black Mask Dinner

![Bob_Houston_HatCropped]() Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018 and was brought back in the summer of 2019.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018 and was brought back in the summer of 2019.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He organized ‘Hither Came Conan,’ as well as Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he contributed to The New Adventures of Solar Pons.